By Sophia Tareen

Using sidewalks as exam rooms and heavy red duffle bags as medical supply closets, volunteer medics spend their Saturdays caring for the growing number of migrants arriving in Chicago without a place to live.

Mostly students in training, they go to police stations where migrants are first housed, prescribing antibiotics, distributing prenatal vitamins and assessing for serious health issues. These student doctors, nurses and physician assistants are the front line of health care for asylum-seekers in the nation’s third-largest city, filling a gap in Chicago’s haphazard response.

“My team is a team that shouldn’t have to exist, but it does out of necessity,” said Sara Izquierdo, a University of Illinois Chicago medical student who helped found the group. “Because if we’re not doing this, I’m not sure anyone will.”

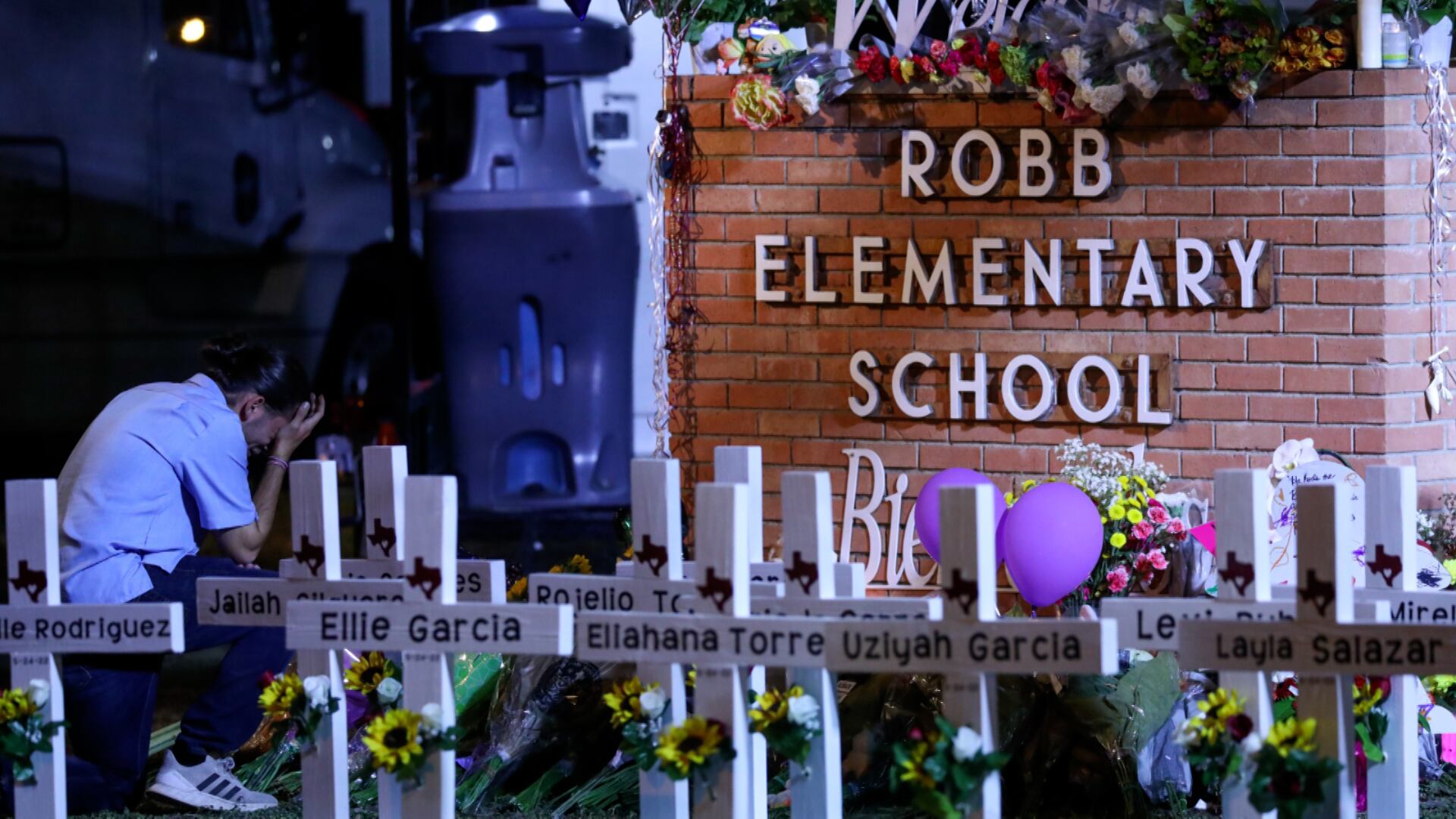

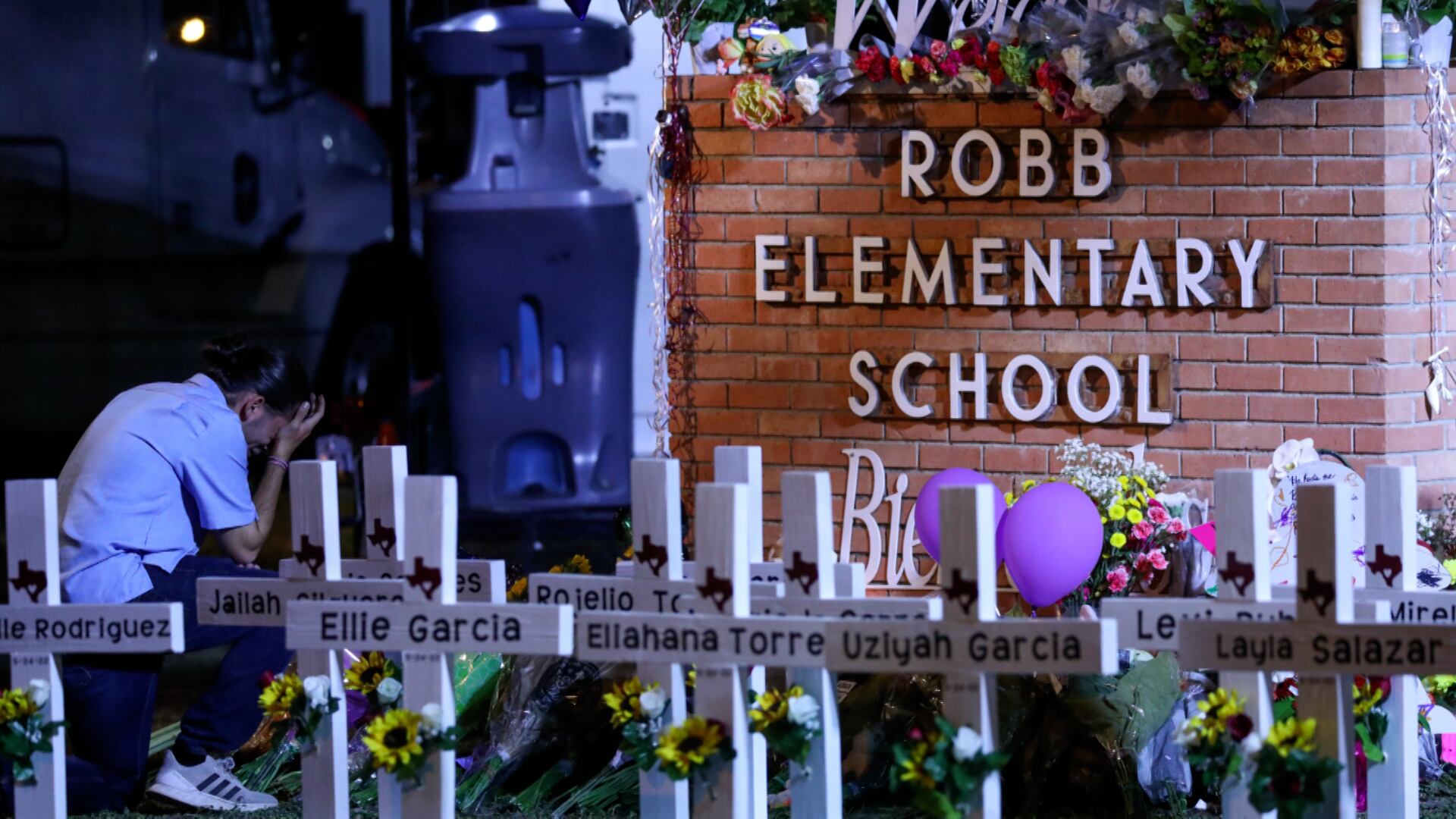

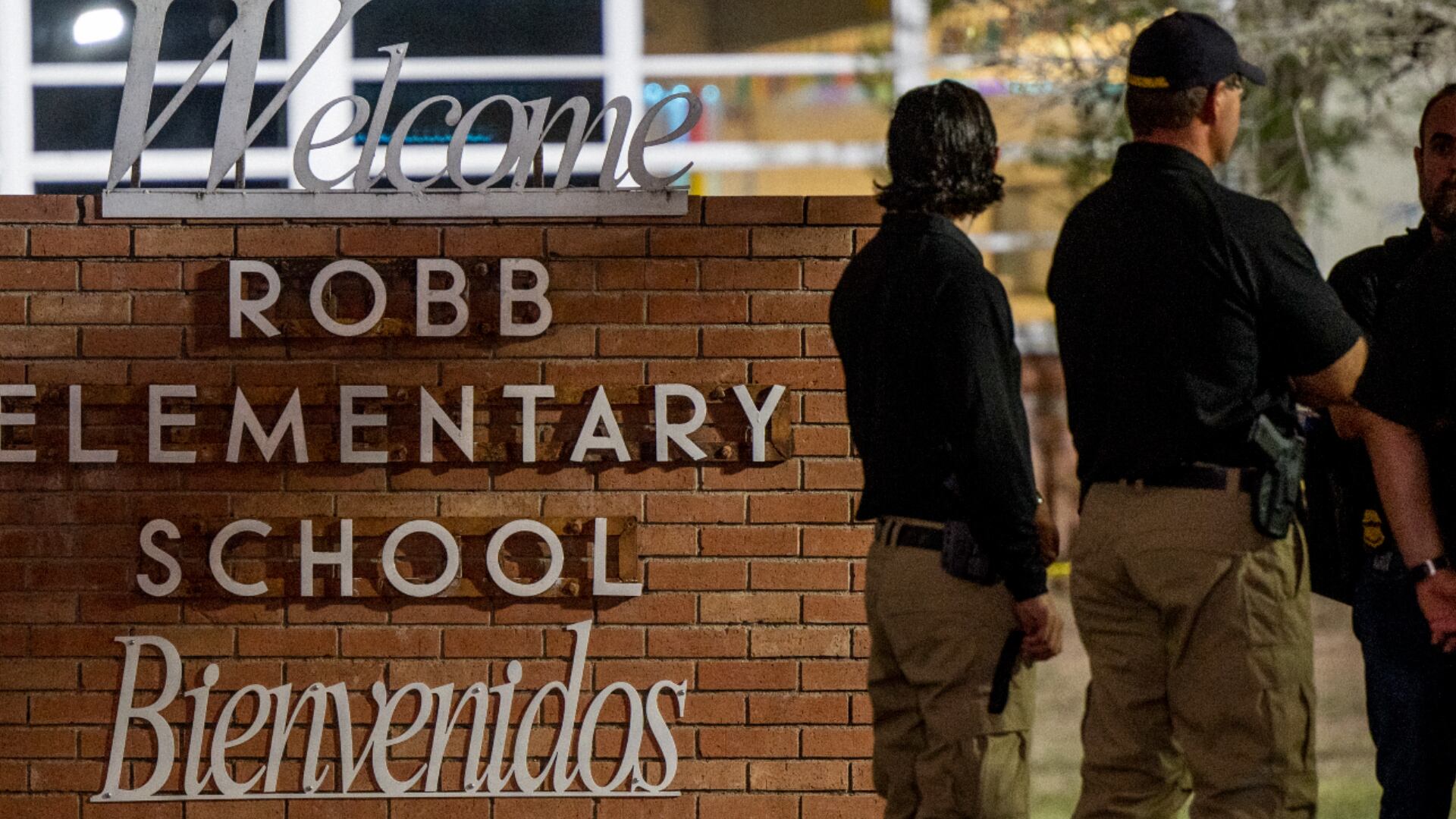

More than 19,600 migrants have come to Chicago over the last year since Texas Gov. Greg Abbott began sending buses to so-called sanctuary cities. The migrants wait at police stations and airports, sometimes for months, until there's space at a longer-term shelter, like park district buildings.

Once in a shelter, they can access a county clinic exclusively for migrants. But the currently 3,300 people in limbo at police stations and airports must rely on a mishmash of volunteers and social service groups that provide food, clothes and medicine.

Izquierdo noted the medical care gap months ago, consulted experienced doctors and designed a street-medicine model tailored to migrants' medical needs. Her group makes weekly visits to police stations, operating on a shoestring budget of $30,000, mostly used for medication.

On a recent Saturday, she was among dozens of medics at a South Side station where migrants sleep in the lobby, on sidewalks and an outdoor basketball court. Officers didn’t allow the volunteers in the station so when one patient requested privacy, their doctor used his car.

Abrahan Balizario saw a doctor for the first time in five months.

The 28-year-old had a headache, toothache and chest pain. He recently arrived from Peru, where he worked as a driver and at a laundromat but couldn’t survive. He wasn’t used to the brisk Chicago weather and believed sleeping outdoors exacerbated his symptoms.

“It is very cold,” he said. “We’re almost freezing.”

The volunteers booked him a dental appointment and gave him a bus pass.

Many migrants who land in Chicago and other U.S. cities come from Venezuela where a social, political and economic crisis has pushed millions into poverty. More than 7 million have left, often risking a dangerous route by foot to the U.S. border.

The migrants’ health problems tend to be related to their journey or living in crowded conditions. Back and leg injuries from walking are common. Infections spread easily. Hygiene is an issue. There are few indoor bathrooms and outdoor portable toilets lack handwashing stations. Not many people carry their medical records.

Most also have trauma, either from their homeland or from the journey itself.

“You can understand the language, but it doesn’t mean you understand the situation,” said Miriam Guzman, one of the organizers and a fourth-year medical student at UIC.

The doctors refer patients to organizations that help with mental health but there are limitations. The fluid nature of the shelter system makes it difficult to follow up; people are often moved without warning.

Chicago's goal is to provide permanent homes, which could help alleviate health issues. But the city has struggled to manage the growing population as buses and planes arrive daily at all hours. Mayor Brandon Johnson, who took office in May, calls it an inherited issue and proposed winterized tents.

His administration has acknowledged the heavy reliance on volunteers.

“We weren’t ready for this,” said Rey Wences Najera, first deputy of immigrant, migrant and refugee rights. “We are building this plane as we are flying it and the plane is on fire.”

The volunteer doctors also are limited in what they can do: Their duffle bags have medications for children, bandages and even earplugs after some migrants wanted to block out sirens. But they cannot offer X-rays or address chronic issues.

“You’re not going to tell a person who has gone through this journey to stop smoking,” said Ruben Santos, a Rush University medical student. “You change your way of trying to connect to that person to make sure that you can help them with their most pressing needs while not doing some of the traditional things that you would do in the office or a big academic hospital.”

The volunteers explain to each patient that the service is free but that they're students. Experienced doctors, who are part of the effort, approve treatment plans and prescribe medications.

Getting people those medications is another challenge. One station visit prompted 15 prescriptions. Working from laptops on the floor — near dozens of sleeping families — the doctors mapped out which medics would pick up medications the following day and how they'd find the recipients.

Sometimes the volunteers must call for emergency help.

Thirty-year-old Moises Hidalgo said he had trouble breathing. Doctors heard a concerning “crackling” sound, suspected pneumonia and called an ambulance.

Hidalgo, who came from Peru after having left his native Venezuela more than a decade ago, once worked as a chef. He’s been walking around Chicago looking for jobs, but has been turned away without a work permit.

“I’ve been trying to find work, at least so that I can pay to sleep somewhere, because if this isn’t solved, I can’t keep waiting,” he said.

To stay warm while sleeping outside, he wore four layers of clothing; his loose pants cinched with a shoelace.

The medics hope Chicago can formalize their approach. And they say they'll continue to keep at it — for some, it’s personal.

Dr. Muftawu-Deen Iddrisu, who works at Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center, said he wanted to give back. Originally from Ghana, he attended medical school in Cuba.

“I come from a very humble background,” he said. “I know how it feels. I know once sometime back someone did the same for me.”

Associated Press video journalist Melissa Perez Winder contributed to this report.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.