By Marcia Dunn

Astronomers have discovered the farthest star yet, a super-hot, super-bright giant that formed nearly 13 billion years ago at the dawn of the cosmos.

But this luminous blue star is long gone, so massive that it almost certainly exploded into bits just a few million years after emerging. Its swift demise makes it all the more incredible that an international team spotted it with observations by the Hubble Space Telescope. It takes eons for light emitted from distant stars to reach us.

“We’re seeing the star as it was about 12.8 billion years ago, which puts it about 900 million years after the Big Bang,” said astronomer Brian Welch, a doctoral student at Johns Hopkins University and lead author of the study appearing in Wednesday’s journal Nature.

“We definitely just got lucky.”

He nicknamed it Earendel, an Old English name which means morning star or rising light — “a fitting name for a star that we have observed in a time often referred to as `Cosmic Dawn.′ ”

The previous record-holder, Icarus, also a blue supergiant star spotted by Hubble, formed 9.4 billion years ago. That’s more than 4 billion years after the Big Bang.

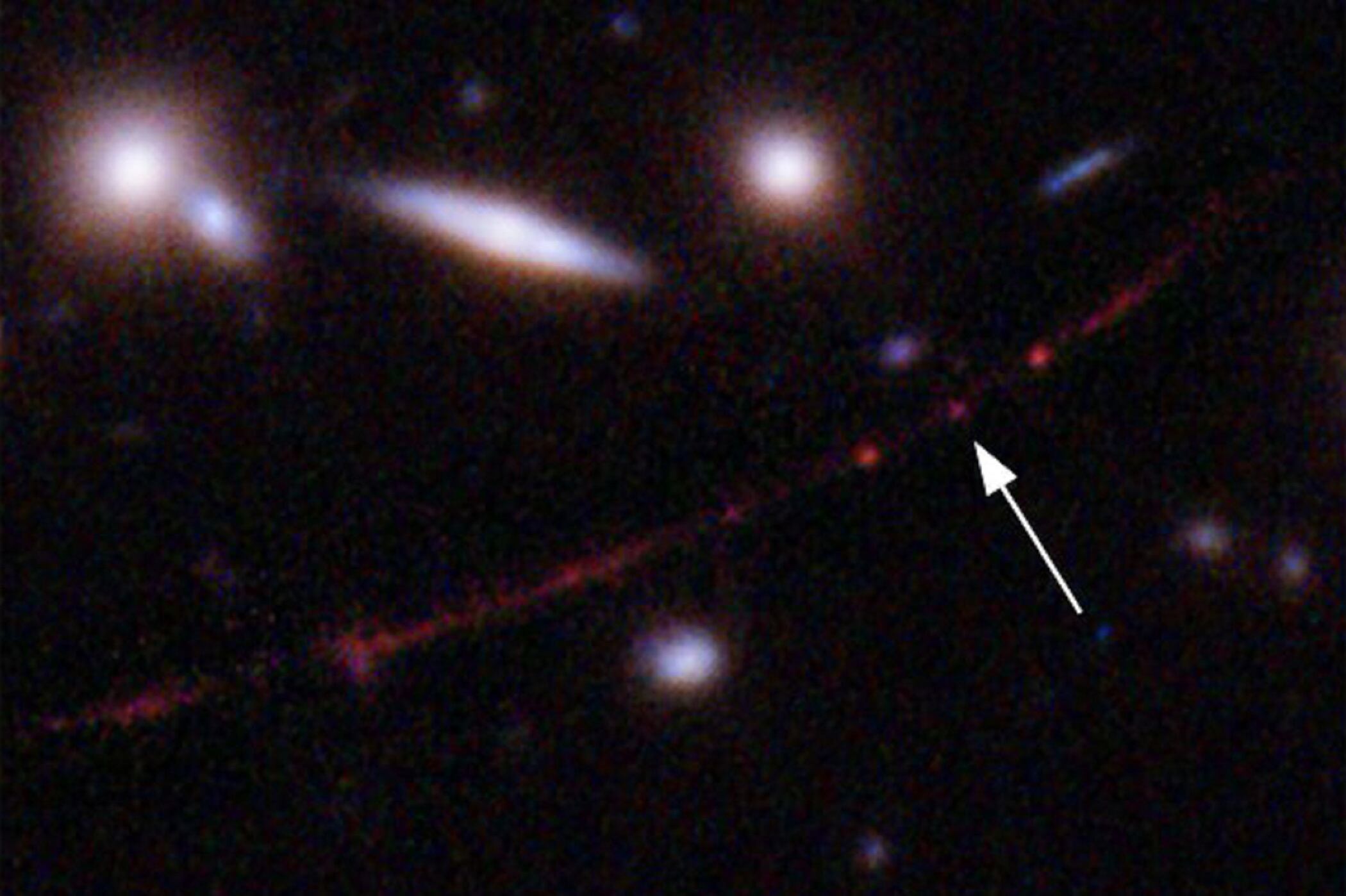

In both instances, astronomers used a technique known as gravitational lensing to magnify the minuscule starlight. Gravity from clusters of galaxies closer to us — in the foreground — serve as a lens to magnify smaller objects in the background. If not for that, Icarus and Earendel would not have been discernible given their vast distances.

While Hubble has spied galaxies as far away as 300 million to 400 million years of the universe-forming Big Bang, their individual stars are impossible to pick out.

“Usually they’re all smooshed together ... But here, nature has given us this one star — highly, highly magnified, magnified by factors of thousands — so that we can study it,” said NASA astrophysicist Jane Rigby, who took part in the study. “It’s such a gift really from the universe.”

Vinicius Placco of the National Science Foundation’s NOIRlab in Tucson, Arizona, described the findings as “amazing work.” He was not involved in the study.

Placco said based on the Hubble data, Earendel may well have been among the first generation of stars born after the Big Bang. Future observations by the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope should provide more details, he said, and “provide us with another piece of this cosmic puzzle that is the evolution of our universe.”

Current data indicate Earendel was more than 50 times the size of our sun and an estimated 1 million times brighter, outsizing Icarus. Earendel’s small, yet-to-mature home galaxy looked nothing like the pretty spiral galaxies photographed elsewhere by Hubble, according to Welch, but rather “kind of an awkward-looking, clumpy object.” Unlike Earendel, he said, this galaxy probably has survived, although in a different form after merging with other galaxies.

“It's like a little snapshot in amber of the past,” Rigby said.

Earendel may have been the prominent star in a two-star, or binary, system, or even a triple- or quadruple-star system, Welch said. There’s a slight chance it could be a black hole, although the observations gathered in 2016 and 2019 suggest otherwise, he noted.

Regardless of its company, the star lasted barely a few million years before exploding as a supernova that went unobserved as most do, Welch said. The most distant supernova seen by astronomers to date goes back 12 billion years.

The Webb telescope — 100 times more powerful than Hubble — should help clarify how massive and hot the star really is, and reveal more about its parent galaxy.

By studying stars, Rigby said: “We are literally understanding where we came from because we’re made up of some of that stardust.”

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.