Many Americans might find it surprising that, in many instances, the colors of certain foods exist as they are because the government said so. The juicy oranges grabbed from the supermarket might not have been actually orange when they were picked from the tree and instead could have been a shade of green when fully ripe.

The culture of dyeing foods particular colors in America dates back to an age-old battle between butter and margarine.

Butter vs. Margarine

Butter was a hot commodity in the 1860s. Expensive and easily perishable, there was a need for an alternative. At the end of the decade, French chemist Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès created a blend of animal fat, milk, and salt that could stand up against butter and took much longer to spoil. The butter substitute was flying off of American supermarket shelves just as fast as the product arrived in the country in 1870.

There was one issue, however. Margarine in its natural state looked like lard, but manufacturers wanted to compete with butter, so they began to color it yellow. Dairy farmers and butter manufacturers already were not fans of the substitute as they watched it cut into their business, and, as a result, a barrage of anti-margarine ads popped up.

The federal government somewhat obliged the U.S. dairy industry by passing the Oleomargarine Act in 1886. Now, margarine manufacturers could still produce a yellow-dyed product, but there was a 2 cent per pound tax imposed on the butter substitute. It's one of the first recorded instances of American businesses using government intervention to stop competition.

The butter industry pursued more regulations, and by the end of the century, more than two dozen states enacted their own regulations on food color. The federal government also bumped the tax on yellow margarine up to 10 cents per pound. To bypass this, factories began using oil to naturally color margarine or including yellow dye capsules in packaging so people could mix their own margarine color at home.

Feds Weed Out Harmful Dyes

The idea of changing or enhancing the color of food was taking off, but by 1906 the federal government passed the Food and Drugs Act, banning the use of harmful food coloring or additives to conceal damaged or inferior products unless it was labeled as such. Seven colors were deemed safe for consumption, including an array of blues, yellows, and greens, although other colorings could be used as long as they appeared on the label. Today, there are nine approved colors.

In the early 1900s, the USDA also began grading food on the quality of its appearance.

“If we don’t use coloring in our food products to look a lot different than they look, it may affect people’s decision whether to buy a food product or not,” explained Michael Roberts, executive director at Resnick Center for Food Law and Policy.

As more food makers tinkered with colors, there was a quest to root out harmful substances and around 1937 the Food and Drug Administration moved to enact the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act after the deaths of more than 100 people, including children, in a medical mishap involving an elixir meant to cure various illnesses. The new law wasn’t just a crackdown on the medical industry; food manufacturers now were only allowed by law to incorporate certified food coloring into products.

Use of Synthetic Food Color Is Fading

Now, think back to that orange you had for breakfast this morning. Thanks to the FDA it is some shade of orange — but, it may not have always been that way.

In warmer locales, typically closer to the equator, ripe oranges are actually green. Most Americans are accustomed to eating orange oranges, so farmers in some states like Florida and Texas may dye or manipulate the fruit’s skin to the bright, glowing shade so popular in supermarket displays. However, states like California and Arizona have banned the practice.

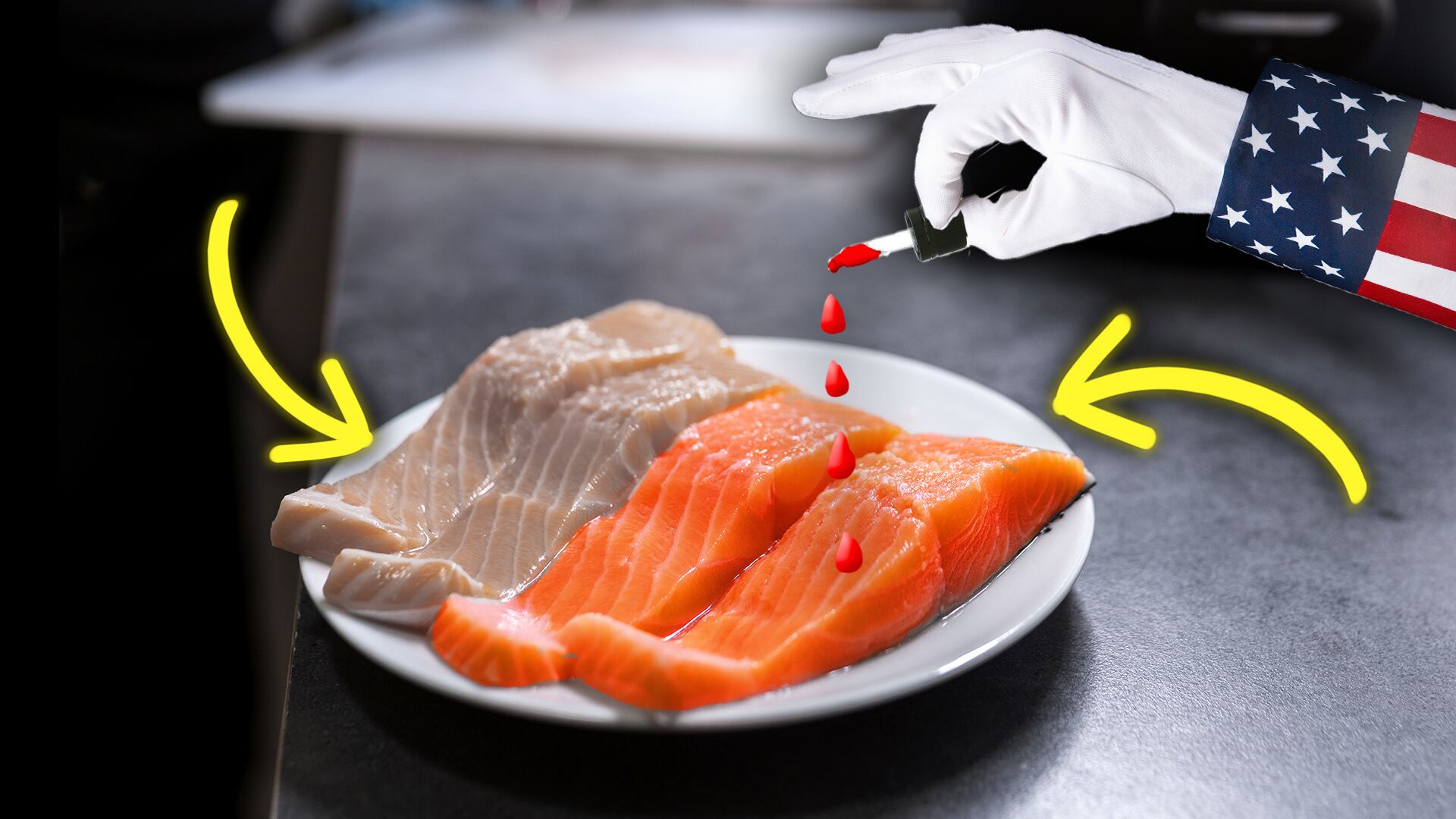

Some of your other favorite food items may also be hiding behind dyes, including microwave popcorn, yogurt, chewing gum, and fish like salmon.

“Fish is a huge problem when it comes to deception. You’ve got fish that’s caught in Alaska for example, sent to Asia for manipulation, sent back to Alaska, and then sent to the States for consumption in sushi bars,” Resnick Center's Roberts said.

Today, the use of food dyes is on a decline. With healthy eating options remaining a priority for both consumers and manufacturers, companies are looking for more natural alternatives, while safety standards allow for some wiggle room.

“The standard the government uses is a reasonable [safety] standard," said Roberts. "So they don’t have to be foolproof, 100 percent proven safe, but they have to be shown to be reasonably safe. So, we allow these little exceptions to the 100 percent rule, no-risk rule, in order to accommodate a modern food system of having foods that are manufactured in different colors and taste in a variety of foods. The problem with that is beyond just the questions of deception and safety is the question of, is this the kind of food system we want.

Video Produced by Christine Beldon. Article written by Lawrence Banton