As a worldwide semiconductor shortage hammers American industries amid a fragile economic recovery, trade groups are reaching out to the Biden administration with pleas for the federal government to put its weight behind boosting production in the U.S.

"Federal incentives for domestic chip manufacturing, along with federal investments in semiconductor research, would have far-reaching benefits for America's economy, national security, supply chain resilience, and global technology leadership," said Dan Rosso, communications director for the Semiconductor Industry Association.

But what exactly can the government do to encourage more semiconductor manufacturing domestically?

Really it can really play two roles, said Alex Williams, economist for the progressive think tank Employ America. In the short-term, it can invest in building new fabrication facilities in the U.S., which lines up with President Joe Biden's proposal to invest $37 billion in the sector.

Longer-term, Williams argues that the federal government can help create greater demand for chips by either buying more semiconductors itself, through agencies such as the Department of Defense, or investing in industries that need them.

This is crucial because what a number of economists believe caused the current shortage is relatively low demand for semiconductors going back to the 2008 crash, and really since the late 1990s, which left the sector unprepared for the stimulus-fueled and chip-hungry economy of 2020.

"The shortage was really produced by the fact that no one had really wanted to invest heavily in new capital goods because of how bad the demand-side environment was," Williams told Cheddar. "The government has a really wide latitude to influence demand conditions in the economy as a whole."

For much of U.S. history, state-led industrial policy — a concept that's gaining currency as the coronavirus pandemic shakes up global supply chains and puts nations in competition with one another for needed goods such as masks and vaccines — has been driven by military spending, and in many ways that approach continues today.

In late 2020, for example, the Defense Department announced that it would start soliciting proposals for the Rapid Assured Microelectronics Prototypes – Commercial (RAMP-C) program, which will provide incentives for companies that develop semiconductor research and production capacity in the U.S.

Then, in early 2021, the agency announced a strategic partnership with GlobalFoundries, one of the largest semiconductor manufacturers in the world, which aims to provide a steady supply of chips for sensitive military applications.

"We are taking action and doing our part to ensure America has the manufacturing capability it needs, to meet the growing demand for U.S. made, advanced semiconductor chips for the nation's most sensitive defense and aerospace applications," said Tom Caulfield, CEO of GlobalFoundries, in a press release.

Do More Chips = More Jobs?

While the discussion around expanding the country's manufacturing capacity has largely centered on geopolitical concerns, such as increasingly tense trade relations with China, there is another goal that proponents of a new industrial policy around semiconductors are emphasizing: new manufacturing jobs in the U.S.

The Semiconductor Industry Association and the Boston Consulting Group released a study in 2020 showing that $50 billion in federal incentives could help produce 70,000 direct jobs and up to 19 manufacturing facilities over the next 10 years.

Based on the industry group's analysis that every direct job in the sector creates nearly five additional jobs, the investment could produce a total of 400,000 jobs within that time frame.

While Biden's proposal is somewhat lower at $37 billion, that's still potentially tens of thousands of jobs in an industry that currently employs roughly a quarter of a million people in the U.S.

Some industry-watchers, however, believe these numbers are optimistic.

Stacy Rasgon, analyst for AllianceBernstein, a global asset management firm and research service, said the average leading-edge facility can cost between $15-20 billion on its own, and that increasingly newer plants are fully automated.

This could mean fewer jobs and more cutting-edge machines overall.

"The dollar amounts they're tossing around right now are not that high to do what it takes to operate in this industry," he said.

In addition, he pointed out that policy makers have to keep in mind that more than just funding is needed to build up the country's semiconductor industry. Any domestic industry would also need talent and local resources, which he said could require education and immigration reform as well.

"If there was no geopolitical issue, I don't think we'd be looking to spend billions of billions of dollars to attract jobs," Rasgon said. "I don't think that's the impetus for the effort, but I do think it's nice icing on the cake."

Some more icing on the cake, according to Alex Williams, is a possible shift in the conversation around job creation that moves away from zero-sum competition with other countries, which has set the tone for the trade war with China.

"I have a lot of optimism about semiconductors and industrial policy generally because they represent a bipartisan way to drive jobs without relying on adversarial trade relations," he said.

The last four or five years were dominated by the idea that if the U.S. is "sufficiently aggressive toward our trading partners, jobs will magically appear in the country," he added. "But that's not going to create jobs unless you're already on that path."

TSMC's New Arizona Factory

In Arizona, there's at least one project underway that could provide a template for future investments in the space.

Last May, the Trump administration scored a big win when it got Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company to commit to building an advanced chip factory in the U.S.

TSMC is the world's most prolific producer of silicon wafers — an essential component that chip designers like Nvidia and Intel are lining up for.

Beyond those wafers, TSMC also dominates the market through its production of microcontrollers, which help systems function together in products like vehicles. In fact, research firm IHS Markit estimates that 70 percent of the global auto industry's supply of microcontrollers originates from TSMC.

TSMC has estimated its investment in this new U.S. plant to be around $12 billion, leading to the creation of 1,600 jobs.

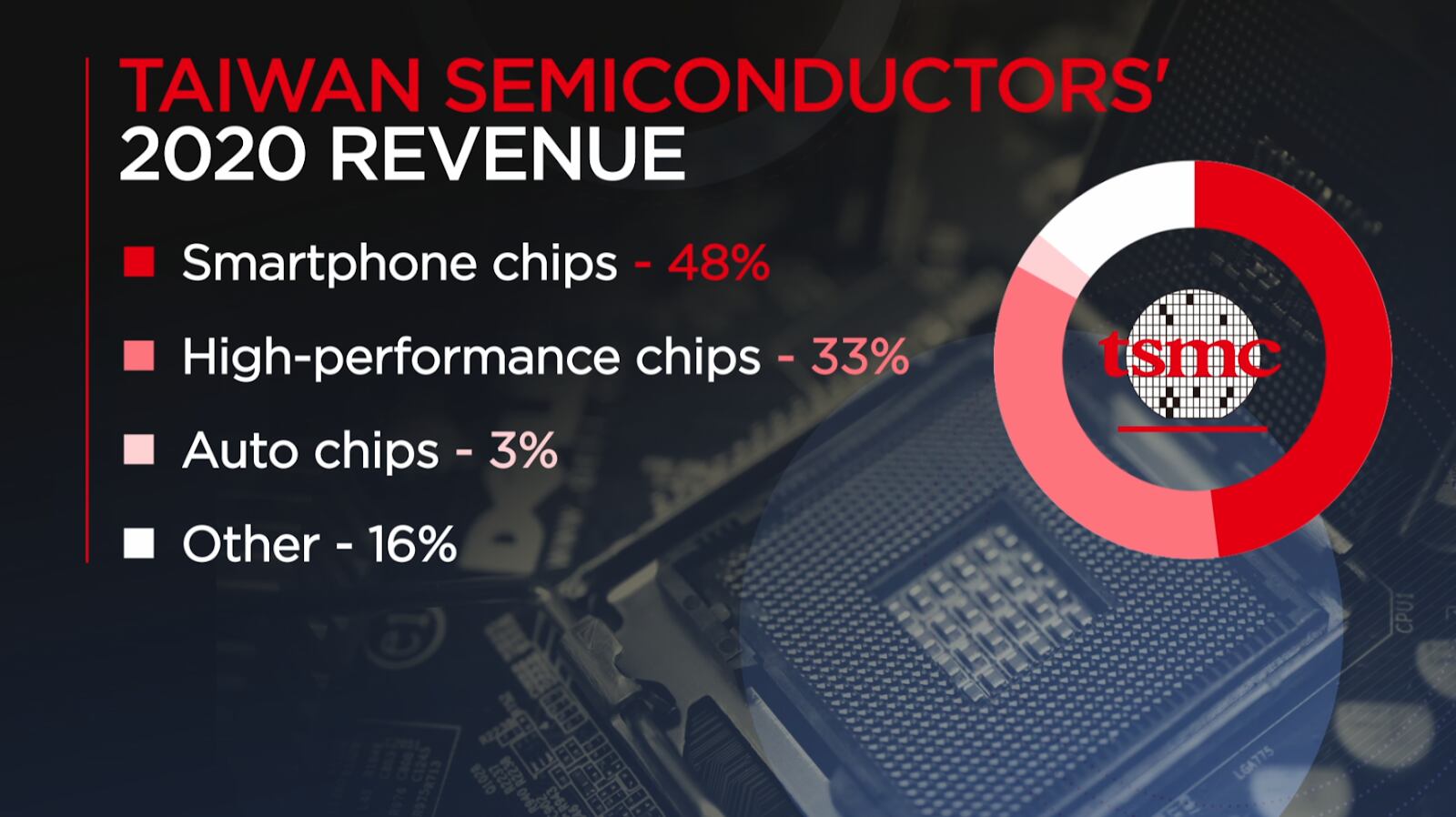

With auto plants around the world having to halt production because of the global semiconductor shortage, TSMC told Reuters there may still be room to prioritize chips for the automotive industry. In 2020, auto chips made up just 3 percent of the company's overall revenue.

TSMC's new factory in Arizona addresses concerns the previous administration had about the world's reliance on a chipmaker that was located so close to economic adversary China.

Another incentive for Taiwan to build this plant on United States soil is for the company to earn the coveted "Made in America" label that many large American companies consider when sourcing materials.

The Biden administration has been pressing Taiwan to resolve the bottlenecks in the global semiconductor supply chain, according to a report from Bloomberg. In response, TSMC executives have told their government that chips for the auto industry will be made a top priority.