By Christina Larson and Seth Borenstein

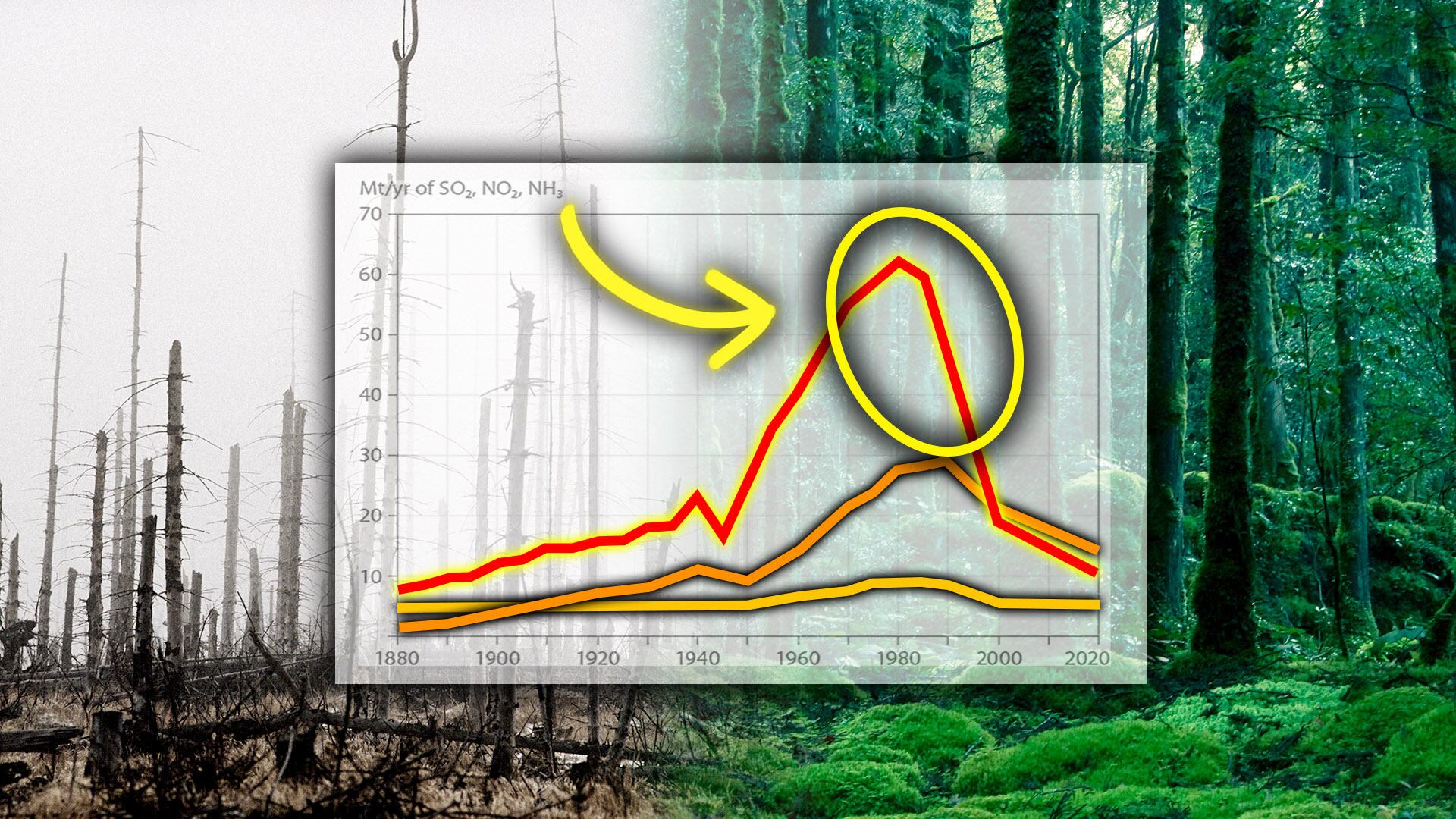

A decade-long global effort to save Earth's disappearing species and declining ecosystems have mostly stumbled, with fragile habitats like coral reefs and tropical forests in more trouble than ever, researchers said in a report Tuesday.

In 2010, more than 150 countries agreed to goals to protect nature, but the new United Nations scorecard found that the world has largely failed to meet 20 different targets to safeguard species and ecosystems.

Six of those 20 goals were "partially achieved," and the rest were not.

If this were a school and these were tests, the world has flunked, said Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, executive secretary of the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity, which released the report.

Inger Andersen, who leads the U.N. environment program, called it a global failure.

"From COVID-19 to massive wildfires, floods, melting glaciers and unprecedented heat, our failure to meet the Aichi (biodiversity) targets — protect our home — has very real consequences," Andersen said. "We can no longer afford to cast nature to the side."

In a Tuesday interview with The Associated Press, former U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon connected the problems to "a lack of global partnership and political leadership." He said multilateralism has been under attack, citing the United States' withdrawal from the Paris climate change agreement as an example.

The U.N. team and report authors said the study is not meant to stoke despair, but to galvanize governments to take stronger actions over the next decade to protect the diversity of life.

"Some progress has been made, but inadequate progress. A lot still needs to be done," Mrema said. "The key is to get the political will and the commitment."

Duke University ecologist Stuart Pimm, who was not involved in the new report, said it's good that countries are getting together to examine their biodiversity goals but some of the targets are nebulous. Reducing "everything on the planet to single scores" obscures the fact that the picture may look different in different places, he said.

For years, conservation activists have used the polar bear as a poster child for species in trouble — especially those threatened by climate change, which the report connects to biodiversity loss. But Mrema and lead author David Cooper said the world should think about a different poster animal: humans.

"A lot of things civilizations depend on are certainly threatened," he said.

The report was originally slated to be released at a U.N. conference to set biodiversity targets for the next decade, but the event in Kunming, China, was postponed until next year due to the pandemic.

Last week, the World Wide Fund for Nature released new research detailing how monitored populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish have declined, on average, 68 percent, between 1970 and 2016.

"With pandemic deaths surging and wildfires raging across the entire West Coast, never have the consequences of our misuse and abuse of the natural world been more clear," said Julia Baum, a biologist at Canada's University of Victoria who wasn't part of the report.

As countries prepare to restart their economies after combating the coronavirus, there's an opportunity to do better — or much worse — for the planet, Cooper said.

"Some countries are relaxing environmental regulations, but others are investing in a green recovery," he said.

One of the challenges in meeting global biodiversity targets is a mismatch between countries with abundant natural assets — such as large tracts of intact tropical forests — and those with money to enforce protections.

"The biodiversity hotspots tend to be in poorer countries," and wealthy countries need to be willing to provide financial or practical support to help other nations, Cooper said.

Dalhousie University marine biologist Boris Worm, who also wasn't part of the report, said the world is at a crossroads.

"We still have the chance to save most of the world's endangered species and vulnerable ecosystems," Worm said. "Now we face a historic choice to either seize this opportunity, and rebuild what has been lost, or to let the world's species slide further into oblivion."

He said it's striking that Earth's biodiversity took millions of years to evolve, "yet we could destroy much of it in a matter of decades — or safeguard it for generations to come."

"It's our choice," he added.

___

AP writer Elias Meseret contributed from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.